Disarming Violence: Decommissioning and the Northern Irish Peace Process

Traditions of Violence

The causes of the Troubles can be traced back to the partition of Ireland in 1921. Following the Easter Rising in 1916 and the Irish War for Independence from the United Kingdom, the island was split by the Anglo-Irish Treaty between North and South, with the southern 26 counties eventually becoming the Republic of Ireland and the 6 counties in the North remaining under British rule. Northern Ireland’s population was approximately 60% Protestant and 40% Catholic, but over the following decades Catholics faced inequalities in housing, politics, and abuse by the Royal Ulster Constabulary police force, which was overwhelmingly Protestant. Catholics and Protestants were also largely divided between issues of nationalism, with many Protestants being pro-Union loyalists (wanting to stay in the U.K.) and many Catholics being pro-republican (wanting to reunify all 32 counties of Ireland). When Catholic civil rights faced confrontations with the RUC and violence from Protestant mobs in 1966, some republicans felt that the old Irish Republican Army, now mostly disarmed, was unable to defend Catholic communities.[1]

The new Provisional IRA began operations in 1969 and was the largest republican group, with smaller factions such the Official IRA and Irish National Liberation Army appearing not long after. Numerous loyalist factions also emerged in this time period, notably the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Ulster Defense Association.[2] Following the deployment of the British Army in 1969, and mass internment of IRA volunteers, republican paramilitaries expanded their armed campaign to fight the military.

For both loyalist and republican paramilitaries, weapons and violence were not just a means for realizing their goals but also an important part of their self-image and propaganda. In the wake of loyalist attacks on Catholic communities, IRA members saw themselves as defenders of that community. The newly formed Provisionals developed a “pride in resistance” against the forces that they saw as oppressive to Catholics in Northern Ireland.[3] For IRA volunteers, violence from Protestants had to be met in kind. As the British military presence increased, the IRA stepped up their war of attrition to advance their other goal of ending British rule and reuniting Ireland. Reformist politics were seen as ineffective and only violent revolution could bring about change.[4] For their part, loyalist paramilitaries also saw themselves as defenders of their communities. They wrongly feared the civil rights marches were smokescreens for an old IRA uprising, but by attacking Catholics, they provoked actual republican violence, therefore confirming their worries in their own minds.[5]

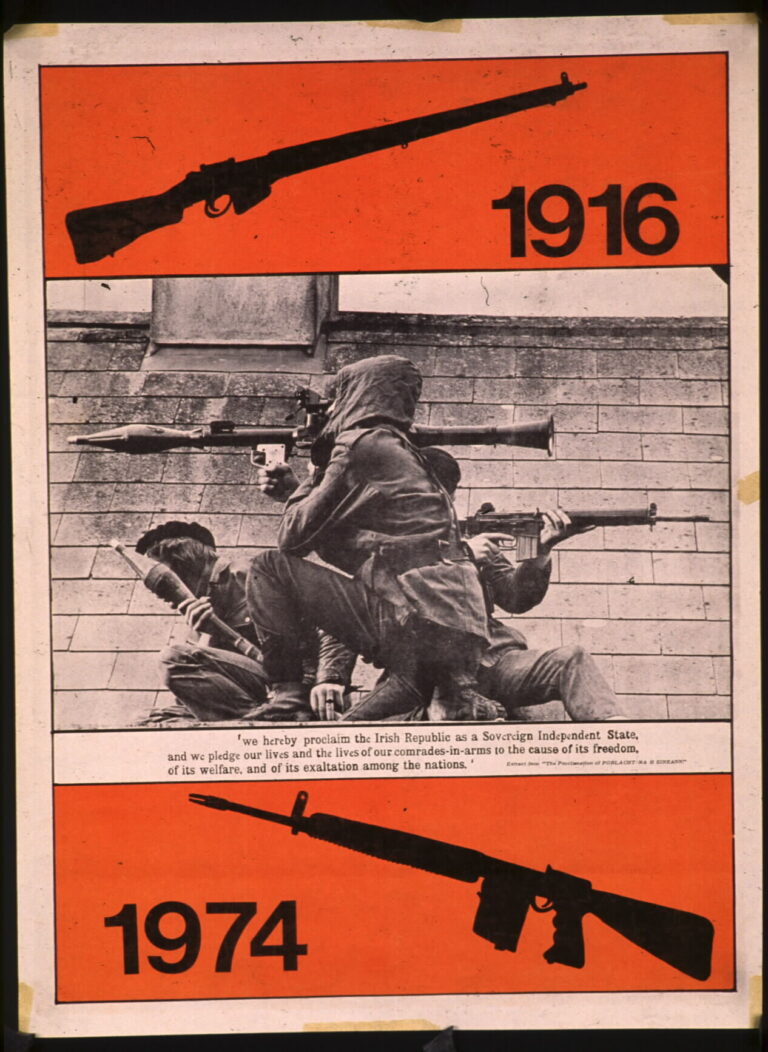

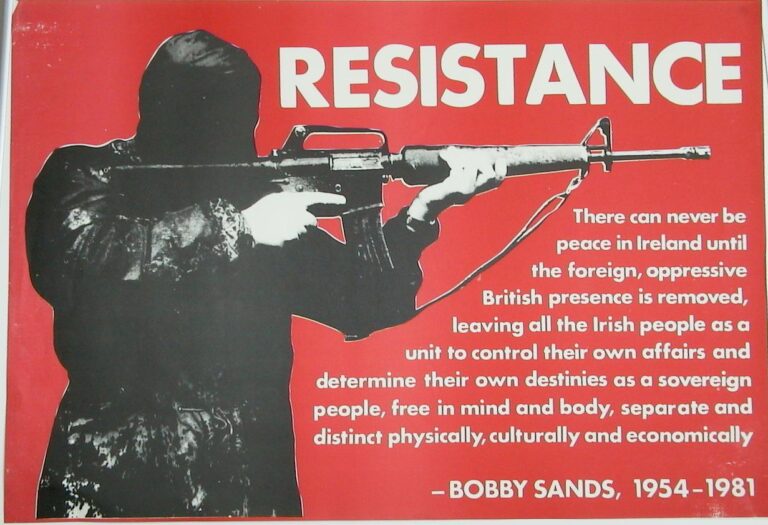

Violence and weaponry also featured prominently in propaganda and media from paramilitaries, which reinforced militant attitudes and distrust between communities. A poster produced by the Provisional IRA around 1974 shows a photograph of volunteers posing dramatically with a rocket-propelled grenade launcher and ArmaLite AR-18 rifles, the latter of which would become a symbol of the IRA. At the top and bottom of the poster, the dates “1916” and “1974” are set alongside silhouettes of old and modern rifles. The dates encourage the viewer to draw a connection between the Provisional and the rebels of the 1916 Easter Uprising, thereby legitimizing the Provisionals as the successors to the Irish republican tradition.[6] Another poster from the 1980s shows a volunteer shouldering and AR-15 rifle with the title “Resistance” and an anti-imperialist quote from Bobby Sands. Many rebel songs from the era make reference to weapons and violence. A notable example is “My Little ArmaLite,” in which the singer proclaims his wish to be “lying in the dark with a provo company” with “a clip of ammunition for my little ArmaLite” so he can repel the British forces from different parts of Northern Ireland.[7] Thus, weapons and violence were ingrained into paramilitary culture during the Troubles, posing a major challenge to those who wanted to end the cycles of violence endemic to the conflict through disarmament.

[1] English, Armed Struggle, 98-115.

[2] Brew, Northern Ireland: A Chronology of the Troubles, 1-17.

[3] English, Armed Struggle, 120.

[4] English, Armed Struggle, 123-124.

[5] English, Armed Struggle, 145-147.

[6] “IRA Poster 1974,” Examples of IRA Posters, CAIN Archive. CAIN Web Service. Accessed 3 March 2022. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/images/posters/ira/index.html.

[7] “Resistance,” Examples of IRA Posters, CAIN Archive. CAIN Web Service. Accessed 3 March 2022. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/images/posters/ira/index.html.